Racing Post journalist Chris Cook covers the use of TPD data in Amo Racing’s appeal against the Norfolk Stakes Result in his latest newsletter. Read the full piece below:

We’re always being told about the importance of being led by the data but it was still slightly surprising to see that piety being pressed into action on Wednesday. It happened during the Norfolk Stakes appeal, at which an attempt was made to identify the impact on Crispy Cat of the interference he suffered from The Ridler, first past the post.

I’ve sat through many, many interference-related hearings (not the sort of boast likely to impress anyone) and can’t recall a lawyer presenting data of this kind before. But I found it interesting and persuasive that Rory Mac Neice, a solicitor engaged by Crispy Cat’s owner, was able to present the panel with specific measurements of the relative speed of both horses during the incident.

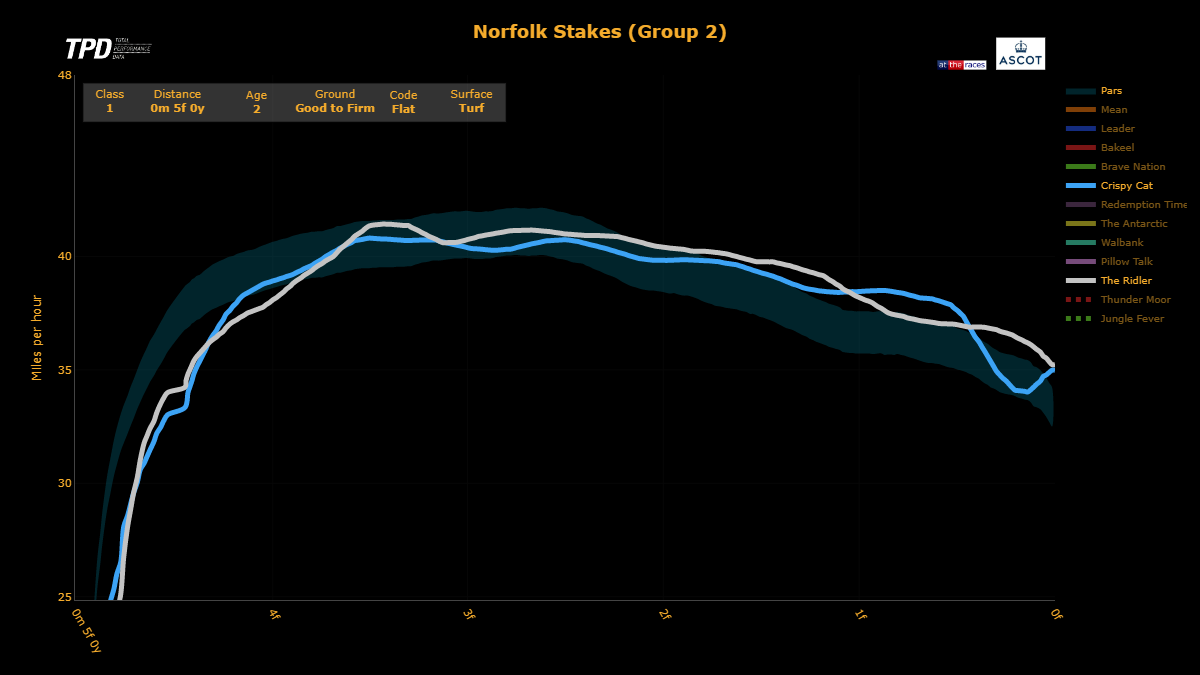

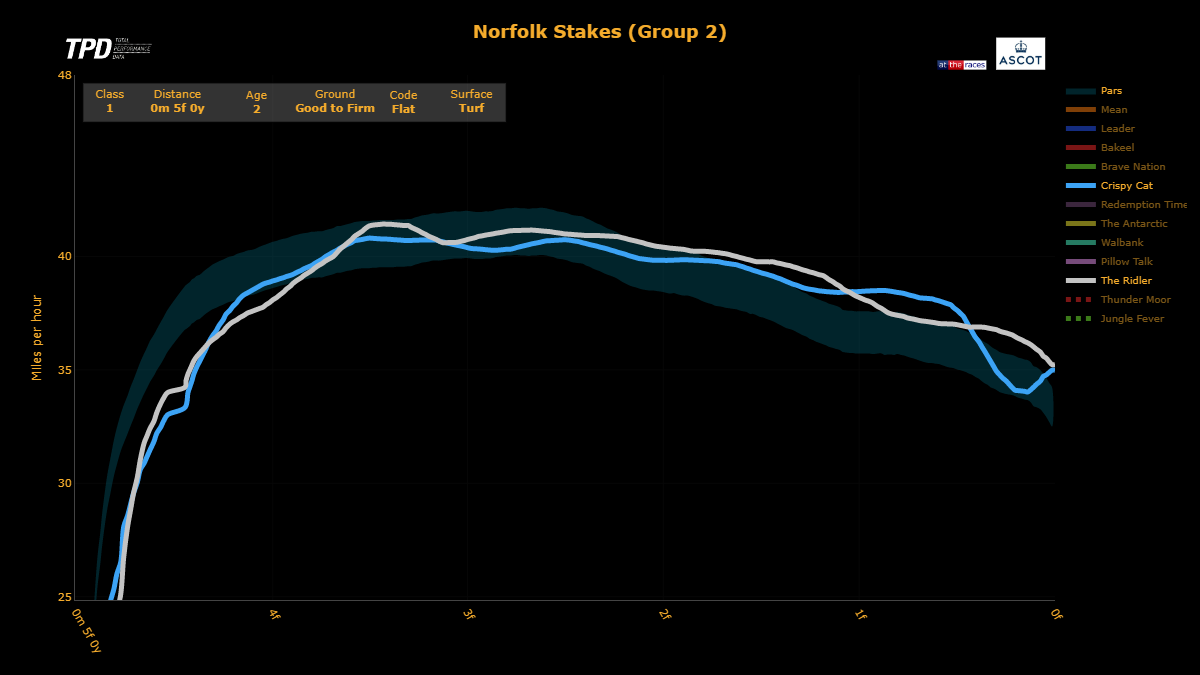

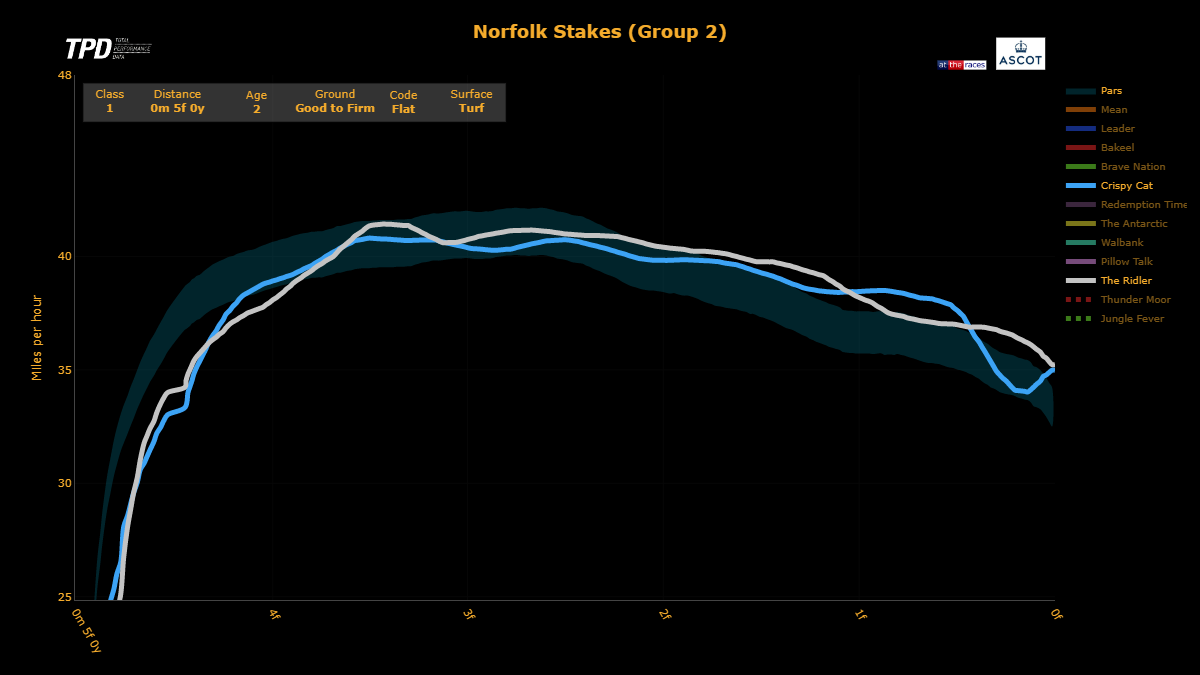

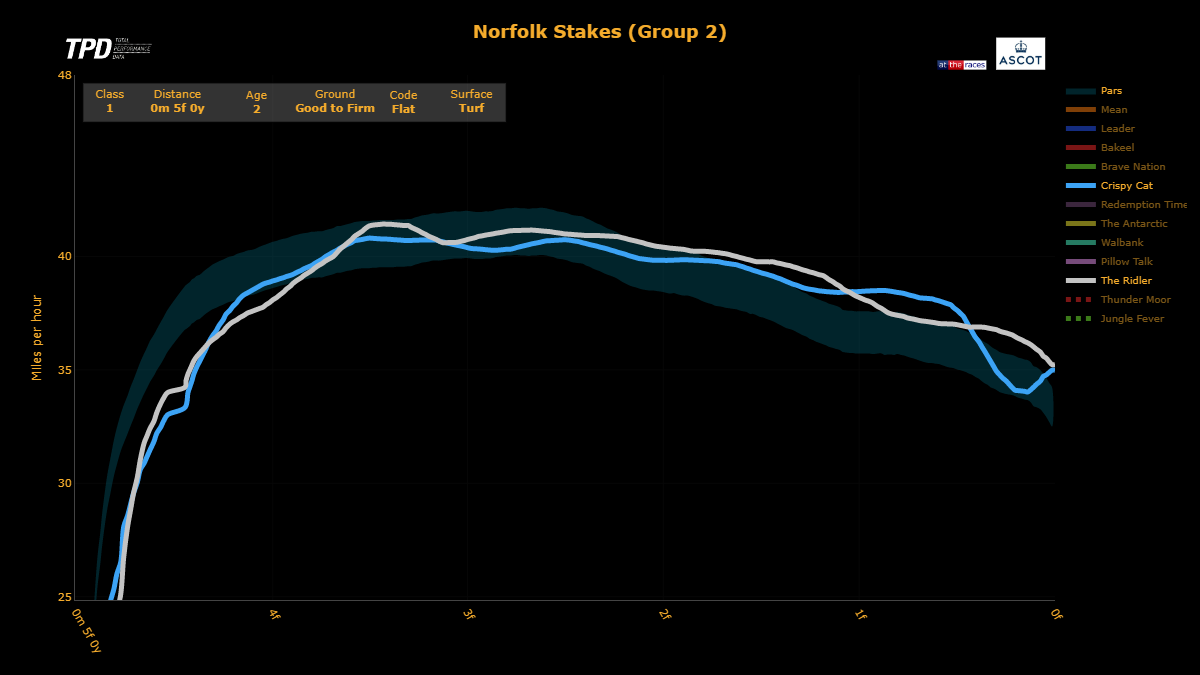

Mac Neice shared with the panel, and onlookers, a graph which traced the speeds of The Ridler and Crispy Cat through the race, at Royal Ascot in mid-June. The Ridler was slightly quicker from an early stage until entering the final furlong but at that point his speed was on a steady downward slope which it maintained to the line.

Crispy Cat became the faster of the two at the start of the last furlong and managed to increase his speed briefly with half a furlong to go. Almost immediately, his speed-line dipped sharply, this being the point where The Ridler crossed in front of him.

His speed dropped from about 38mph to about 33mph, the slowest he had been moving since accelerating away from the stalls. When the interference finished, he was able to quicken again to 35mph but his chance had gone.

It was a fascinating and thought-provoking addition to the replays of the race which are always a staple of interference hearings. The impact on Crispy Cat, represented by the graph, struck me as being a lot more dramatic than what I had seen in the footage. As Mac Neice put it to me: “The footage of the race gives a sense of what happened, the data gives perspective.”

Naturally, the BHA’s barrister wanted to minimise the importance of the data evidence. The BHA’s position is that the stewards reached the right decision in allowing the result to stand, that Crispy Cat would probably not have won even with a clear run.

So the BHA response was that the data presented was incomplete. There should (they maintained) also have been some extrapolation showing what time Crispy Cat would have achieved without the interference.

Such a calculation ought to be possible, according to Will Duff Gordon, chief executive of Total Performance Data, whose data was in the graph. He told the Front Runner: “I’m interested in saying, can we work out what the expected finishing time of these horses was, based on their velocity per second, based on how we know horses decelerate up the hill at Ascot?

“The mathematics is all very doable with good data science and a good body of history and we have half a million horse performances in our database. We’ve got Ascot data for three years.”

But even without that, he says the data presented on Wednesday is a valid addition to the information available to the panel and can guide their decision. “The bare data should be used and rigorously assessed. You can’t just sit back and say, it’s too complicated.

“One of the reasons the Levy Board invested Racing Foundation money, which is punters’ money, in the expansion and rollout of sectional timing was because the benefits are myriad. It helps broadcasters, in-race gambling, pre-race gambling and then one day there’s the automated interpretation of interference.

“Of course that will take many years to get right but it’s exciting to think we can help stewards have some objective data.”

Mac Neice was clear, when we spoke yesterday, that he did not want to go over the details of the Norfolk Stakes again. The various arguments have been presented to the panel which must now form its own decision, likely to be delivered next week.

But he agreed with me that graphs like the one he produced this week might become a regular feature of such hearings in future. “It perhaps provides data points that can illustrate loss of momentum and therefore the impact of interference,” he said, with a lawyer’s caution.

I’m all for it, having sat through so many hearings where the eventual verdict seemed a bit guessy. We’ve all been in that situation, where you and your friends see a controversial finish and all form different opinions about what would or should have happened.

It’s profoundly unsatisfying not to have any ultimate source of a wholly convincing verdict, someone impartial, deeply knowledgeable, with unimpeachable judgement. I suppose what I’m asking for is God to tell me whether it should have been The Ridler or Crispy Cat, Sire De Grugy or Special Tiara, insert your own vexed memory here.

Until God pipes up, the data will have to do. It’ll be pretty interesting if TPD develops software that can tell us what time the victim of interference would probably have achieved with a clear run. If that ends up being reliable enough and fast enough, stewards might one day be freed of the whole wretched business of judging who ought to have won.

“Rather a messy finish,” one of them will opine as the runners are being pulled up. “Are we going to have to change this result?”

The stipendiary steward beside him presses a couple of buttons. “Computer says no.”